I am pleased to announce that as of last Saturday I am a college graduate! It has been quite a while since I have written a blog and I haven't kept everything as up to date as I would have liked. So here is my best attempt to wrap up loose ends.

My last semester at Ohio University has been quite the whirlwind as I am sure any 2020 graduate can attest. To get the low-notes out of the way, Covid-19 has kept even us wildlife students cooped up inside (more or less). It has been a bizarre and a far-from-painless transition to online learning, but we roll with the punches. The online lectures, coursework, and finals have pretty well blurred together and it's an incredible relief to be free of them (hopefully for good).

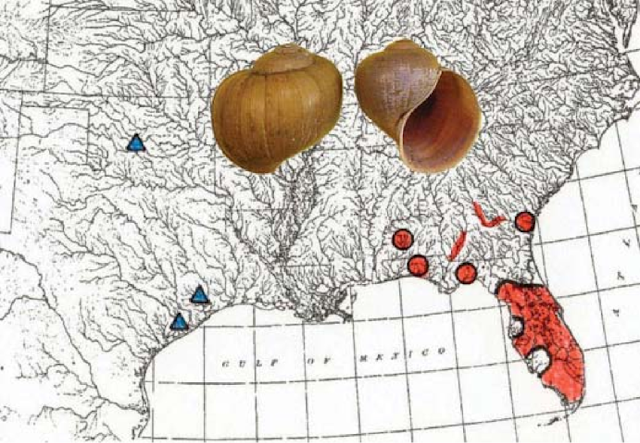

Most of the time I would have dedicated to writing blogs this semester was consumed with writing my Senior Honor’s Thesis, which I recently completed and had accepted. I don’t recall how much I have talked about this project on the blog, so here is a little background information. I started work on what I have been proudly referring to as “Snakes on a Lane” late in my sophomore year. Together with the help of my advisors, Dr. Viorel Popescu and Dr. Carl Brune, I have analyzed a long-term data set of snake road mortality points to establish hotspots where snakes face an increased likelihood of being run over. With my manuscript completed, we hope to publish in a herpetological journal.

I have been hesitant to announce any of my future plans with the global pandemic throwing everything into uncertainty; but I am tentatively confident that almost everything is a go. A few months prior, I was accepted into the Ohio State University’s School of Environment and Natural Resources Graduate Program. I will be starting my master’s in Dr. Bill Peterman’s Lab working on the Ecology and Conservation of the Common Mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus), Ohio’s second largest salamander. I am beyond excited for this new experience. Finding the right grad school was a tedious, drawn-out process and I feel extremely lucky to have found this project and opportunity. I will be a fully funded student for three years (which means no TAing!) and will be conducting mark-recapture surveys for mudpuppies in hopes of better understanding their survivorship and demographics around Columbus. I will then be working in Northeastern Ohio to determine the potential effects of TFM (a lampricide used to kill the invasive sea lamprey) on mudpuppies. There is also the potential for environmental DNA work. I am extremely eager to start this new chapter in my academic career.

Last month, I was accepted to serve on the board of the Ohio Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (OHPARC). This is an amazing opportunity to learn about and partake in the herpetological work being done throughout Ohio. I feel very grateful to have been asked to join this group and look forward to contributing to the study of herps in the state.

My last big announcement is not 100% official with the inevitable hiring freeze associate with Covid-19, but I was recently hired to write for the ODNR’s Wild Ohio Magazine and other DNR publications. Hopefully once things return to some semblance of normalcy, I will begin to write natural history articles for the magazine (potentially accompanied by my photographs).

The remainder of this blog is dedicated to all the people who made my success as an undergraduate possible. Without the help, encouragement, and camaraderie of those around me, I could not have hoped to be where I am today.

My endless thanks go to my advisor Dr. Viorel Popescu. I first met V (I was much too scared to call him that for about two years) as a freshman. He and Marcel Weigand hired me for my first official wildlife tech job that summer which stands as one of the best experiences I have ever had. Some time in my second year, Viorel suggested I work on an Honor's thesis with the added goal of getting an undergrad publication. He spent many long hours explaining coding and mapping to me and was alway enthusiastic and encouraging. He has been a phenomenal mentor and I really hope to work with him again in the future.

I must also make mention of the Popescu lab. This wacky, quirky group of graduate students and undergrads has been like a second family to me. I will never stop being inspired by their passion and dedication to wildlife and science.

I must specifically thank my fellow Box Turtle researcher team, Christine Hanson, Andrew Travers, Eva Garcia, and all the volunteers. You guys made those hot, humid, and tick infested months unforgettable. I start to get misty eyed just thinking of our adventures together, creating lists of the ridiculous made-up rules like "NO BREAKS," or the unexpected snakey finds hidden among the undergrowth. I'll miss Eva and my lab movie nights, or bickering with Christine because I took a wrong turn. I wish you all the best of luck with your future endeavors and hope we will get out in the field again one day soon.

And of course, Marcel Weigand. It is hard to put into words the kind of person, mentor, and friend Marcel is. She is probably the most caring, compassionate, and fiercely loyal person I have ever met. I hope to emulate her endless love for the Box Turtles that we spent so much time following around in the woods in all my future studies. You have always been able to remind me of the humanity in everyone, even when it isn't easy. Your tenacity is an inspiration and I am constantly reminding myself how lucky I am to have you in my life.

If I could one day be half the herpetologist Carl Brune is I'd be satisfied (and he is a physicist!). I cannot begin to thank Carl enough for all the knowledge he has imparted on me over the last few years of herping across southeastern Ohio. I can confidently say he has taught me everything I know about the reptiles and amphibians of my home state and beyond. Quarantine herping has made me miss our conversations about everything under the sun as we drive between hiking spots. I will always be grateful for your mentorship and friendship. And of course thank you for sharing your data with me and helping me to complete my Honor's Thesis. I can't wait to get back out in the field with you. How's Friday?

I must also thank Dr. Don Miles (DOMI) and Dr. Matt White for their wisdom, humor, and advice. I'll never hear the song American Woman without also hearing Miles' sing "American Bittern," or see a Cedar Waxwing without wondering why it's "the bird that rocks." As for Dr. White, "checking the lip" will be the first thing I do whenever I see a fish (regardless of whether its a creek chub or not).

Thanks to Charlene Hopkins for bringing me out in the swampy backwoods to catch frogs, newts, salamanders, and to sex snapping turtles. Oh, and to peal roadkill off the asphalt. It might not sound like fun to some, but mornings at the wetland were my favorite part of the week. You taught me so much about the world of science and academia my freshman year and I will always be grateful to you for that. I hope your future is full of biting turtles and stinky ponds.

Thanks to Matt Kaunert for showing me my first Snot Otters. Getting out in the field with you was some of the most fun I have had. I really hope to join you in the streams again soon! I need me some Cougar Bob's and I can hear Tidioute calling my name.

So much thanks to Krissy Harman for always taking the time to answer my questions and teach me about careers in wildlife. My resume would be a shadow of itself without your help and insistence that I don't "sell myself short." I've had a great time getting out to do field work with you (though I won't miss the hard hats). Once quarantine is over we need to get back to our Thai Paradise gossip sessions.

Thanks to Holly Latteman. Sorry I didn't listen to your warnings not to catch snakes in South Carolina. You are one of the most encouraging and sweet people I have ever been lucky enough to know. Thanks for being our field mom in ornithology. You were a wonderful TA. Stay in touch! We gotta go Butt Birding soon!

I'm not crying, you're crying. Amanda Szinte, Kathleen Cook, Remington Burwell, Sam Kukor. You guys have been some of the best friends a guy could ask for. We struggled through classes, exams, and field trips together for the past four years. Without your friendship, college would be unrecognizable. You guys inspire me every day to follow my passions and be the best I can be.

Kathleen and Amanda, I will never forget meeting you two at Darwin's birthday freshman year. Who would have guessed what all lay in store for us back then. We made it through some real hurdles together and I know I am the better for it because I was with you two. I cannot wait to hear where wildlife takes you.

Rem and Amanda, I will alway cherish our strange "Rymandington" friendship which no one understood when we went to Ecuador. Can you believe that was two years ago now!?

Sam, I will dearly miss you forcing me to study at the library late at night before exams. I still have all our fish flashcards somewhere. I have obliterated CVA from my memory so I don't have anything to say about that. Remember when we waited till the last minute before Thanksgiving break to do our independent fish seining project? We had to identify 30 shiners by the light of our headlamps and that creepy motel behind the stream. I want a rematch in Drawful. I assume you want a rematch in Smash Bros since I am so amazing at it. Take care bud, I hope those plants and stuff take you far.

Thank you to all my fellow OU Wildlife Club Officers, Maddy Sudnick, Sam Kukor, David Cole, and Kadie Omlor. You guys put in so much time and heart, even when it was thankless and a little unrewarding. I appreciate you guys so much. Thanks for making this club great!

And last, but of course not least, Julia Joos. I know you hate this kind of thing so I will try to keep it brief. Thank you for being the coolest partner in the world. I am in awe of your love for and knowledge of turtles. You are so endlessly encouraging, supportive, and understanding. I could have a conversation with you for hours and not even notice the time pass. I can't wait for our next adventure together.

Oh, and special thanks to my parents, Nikki and Steve Wagner. You are the real reason any of this is possible. You have always done everything in your power to make my dreams come true. You can get excited about anything, make warm-hearted jokes in the toughest of times, and are always there to listen and be supportive. Thank you for everything.

Also Coco and Pima for being very cute baby tortoises.

Also Coco and Pima for being very cute baby tortoises.

Thanks for reading

Hopefully many more adventures to come!

RBW