|

| The Magee Limpkin feeding on a snail in the genus Pluerocera. |

In early July 2019, a juvenile Limpkin turned up outside of Akron, Ohio, superseding the species’s most northerly US record from Maryland in June of 1971 by nearly 250 miles. News of the state record spread throughout the birding community, and by nightfall, a binocular-clad crowd had gathered around the suburban pond where the young bird was calmly feeding on snails. Reports soon flooded in that this was no isolated incident, either. Just a few days earlier, another bird had been seen in Mentor, Ohio. One month later, a third Limpkin was reported from Magee Marsh, and in mid-October, a fourth from Mentor’s Veteran Memorial Park.

|

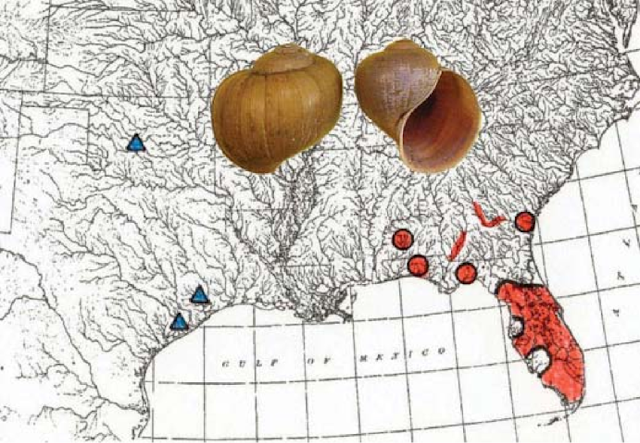

| Range Map of the Limpkin in North America (Source). |

The Limpkin (Aramus guarauna) is the only member of its genus Aramus. Cross the long legs and serpentine neck of a heron with the skulking gait and plump body of a rail and you will have something that quite resembles a Limpkin. These brown and white birds are inhabitants of southern swamps from Florida to Central and South America where they specialize on apple snails (Pomacea sp.) and other freshwater mollusks. With such a specialized diet, it’s a small miracle that the Limpkin has survived the draining and dredging of its wetland habitat. Limpkin population trends are poorly understood, but the species appears to be stable in Florida. Recent declines in the northern portion of its range may represent a contracting distribution, and historical records suggest the Limpkin once inhabited Mississippi, Texas, and much of Georgia.

Sightings of Limpkins north of Florida and extreme southern Georgia are rare, but records of vagrant Limpkins reaching northern latitudes date back to 1950s when an injured bird was found in Nova Scotia, Canada. Sightings of Limpkins in northern latitudes are typically one-offs and are short-lived. The Magee Limpkin on the other hand, has been seen on and off for nearly five months.

Ohio isn’t the only state in 2019 to see its first Limpkin record. In August, Illinois’ first confirmed Limpkin was spotted on a lake near the city of Olney. In 2017, Louisiana had its first Limpkin record when a group of four appeared in December. The following month, a pair successfully reproduced for the first time in the state. This represents breeding nearly 350 miles west of the nearest confirmed breeding record. Two years earlier, Georgia had its first state breeding record near Albany. Decade long surveys suggest that vagrant Limpkins have been turning up with increasing regularity since the early 2000s. Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina have seen the bulk of these vagrants, but Limpkins have found their way to Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Mississippi, and now Louisiana, Illinois, and Ohio.

A bird turning up outside of its natural range is nothing special. Major weather events like hurricanes can blow birds off course, landing them in states where they have rarely or never been recorded before. In 2013, a Brown Pelican, a native of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts, awed birders when it spent the summer along Lake Erie after being swept up by a low pressure system. It represents only the third record of a Brown Pelican in the entire state.

For recently fledged birds, migration has a steep learning curve. Juvenile Scissor-tailed Flycatchers follow their parents as they use visual, magnetic, and celestial cues to navigate. These internal compasses allow them to travel from the prairies of central North America to the southern Caribbean and back each year. During these travels, juveniles can often become disoriented, landing them well outside the usual range for their species. Migration is not all learned either. Sometimes, a genetic mutation can cause a bird's internal navigation system to go haywire. This may partially explain why scissor-tailed flycatchers (as well as many migratory species) occasionally deviate from their set migratory trajectory and have been sighted across North America from Alaska to Nova Scotia.

Then there are the dispersers, which Joseph Grinnell described as “the exceptional individuals that go farthest away from the metropolis of the species; they do not belong to the ordinary mob that surges against the barrier, but are among those individuals that cross through or over the barrier.” Dispersers travel farther than 90% of the population and are responsible for the rapid colonization of human-introduced species like the European Starling and House Finch. How else would birds that rarely travel farther than 50 km in a lifetime colonize eastern North America from one, small founding population in just a few decades?

Due to its exploratory nature, dispersal is a highly risky endeavor, and many birds do not survive their forays into unknown territory. In 2018, a juvenile Great Black Hawk, a species native to central and South America, was found in Maine. It represents the first and only record of a Great Black Hawk in the US. Just why this bird traveled from the tropics to the northern forests is a mystery. The hawk was able to sustain itself on a diet of gray squirrels throughout the summer, but as winter encroached, the tropically-adapted bird suffered severe frostbite and later died in a rehabilitation center.

When successful, dispersal acts as a positive feedback loop for population growth. Lucrative years of reproduction increase the odds some juveniles will be genetically predisposed to wander. Establishment of new populations by a few lucky dispersers bypasses the slow expanse of home range leapfrog that most individuals employ to avoid inbreeding. Newly colonized habitats are not subject to the same limiting resources that stall population growth, allowing a rapid expansion of the species across a wide geographic area.

So what is responsible for Ohio’s sudden Limpkin mini-invasion? Limpkins are non-migratory birds, and the first sighting in early July and August precede the hurricane season. Following sightings have not been linked with any major storm events. A single Limpkin might indicate a faulty navigation system, but mutations are rare events and are unlikely to account for the multiple Limpkin arrivals in northern states. Juvenile birds dispersing from their natal territories seem the most likely explanation.

|

| Range of the native Florida Apple Snail (Pomacea paludosa). (Howells 2006). |

|

| A large invasive Island Apple Snail from Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge in Florida. |

|

| Range of introduced Island Apple Snail (Pomacea maculata formerly P. insularum). (Byers 2013). |

The invasive P. maculata is a tropical species, and while it is currently limited to a handfull of southern states, climate change is poised to expedite its invasion. On average, ten new P. maculata populations are discovered each year. Many biologists feared that the replacement of the native Florida Apple Snail with its larger, tropical relative would spell doom for apple snail specialists like the Limpkin and the endangered Florida Snail Kite (Rostrhamus sociabilis). These larger snails are harder for juvenile Snail Kites to handle, reducing their ability to forage and, in extreme cases, leading to starvation.

What is truly remarkable, however, is that these hardy invasive snails seem to be supplementing the declining native P. paludosa and have jump started Limpkin and Snail Kite population growth. Both species have been documented readily feeding on invasive snails, and the latter may even be adapting to this novel prey (Snail Kites are increasing in body size and bill length). The introduction of P. maculata into novel watersheds has been directly linked with Limpkin range expansion. Limpkins were once exceedingly rare in Lake Seminole, Georgia, but following an unprecedented increase in P. maculata, some twenty birds were recorded in 2017. The first Limpkins to breed in Georgia did so within 5 km of the first P. maculata colony to become established in the state. Nearly all vagrant Limpkins in Georgia, South Carolina, and Alabama have turned up in watersheds that have known populations of invasive apple snails.

|

| Snail Kite from Loxahatchee. |

So there we have it; a growing population in the stronghold of their range has allowed Limpkins to disperse into new regions of the country. Even the small, imperiled population of Snail Kites seems to be following this trend. In October, the first record of a juvenile Snail Kite was reported from Presque Isle, Pennsylvania. But will these birds survive in the northern latitudes? Ohio has no native or invasive apple snails. While we do have our own introduced species of large snail, the Chinese Mystery Snail (Bellamya chinensis), our winters can drop well below freezing for months on end. Establishment of a new Limpkin population in the northern US is extremely unlikely. The best we can hope for at the moment is that our vagrant birds will leave for the winter, and if Limpkin populations continue to grow and expand in the southern US, Limpkins may become increasingly common Ohio vagrants.

|

| Limpkin from Loxahatchee feeding on a mollusk. |

References

Bloom, P. H., Scott, J. M., Papp, J. M., Thomas, S. E., & Kidd, J. W. (2011). Vagrant western Red-shouldered Hawks: origins, natal dispersal patterns, and survival. The Condor, 113(3), 538-546.

Byers, J. E., McDowell, W. G., Dodd, S. R., Haynie, R. S., Pintor, L. M., & Wilde, S. B. (2013). Climate and pH predict the potential range of the invasive apple snail (Pomacea insularum) in the southeastern United States. PLoS One, 8(2), e56812.

Cattau, C. E., Fletcher Jr, R. J., Kimball, R. T., Miller, C. W., & Kitchens, W. M. (2018). Rapid morphological change of a top predator with the invasion of a novel prey. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2(1), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0378-1

Cattau, C. E., Martin, J., & Kitchens, W. M. (2010). Effects of an exotic prey species on a native specialist: Example of the snail kite. Biological Conservation, 143(2), 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2009.11.022

Chaine, N. M., Allen, C. R., Fricke, K. A., Haak, D. M., Hellman, M. L., Kill, R. A., ... & Uden, D. R. (2012). Population estimate of Chinese mystery snail (Bellamya chinensis) in a Nebraska reservoir.

Cottam, C. (1936). Food of the limpkin. The Wilson Bulletin, 48(1), 11-13.

Dobbs, R. C., Carter, J., & Schulz, J. L. (2019). Limpkin, Aramus guarauna (L., 1766)(Gruiformes, Aramidae), extralimital breeding in Louisiana is associated with availability of the invasive Giant Apple Snail, Pomacea maculata Perry, 1810 (Caenogastropoda, Ampullariidae). Check List, 15, 497.

Greenwood, P. J., & Harvey, P. H. (1982). The natal and breeding dispersal of birds. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 13(1), 1-21.

Horgan, F. G., Stuart, A. M., & Kudavidanage, E. P. (2014). Impact of invasive apple snails on the functioning and services of natural and managed wetlands. Acta Oecologica, 54, 90-100.

Howells, R. G., Burlakova, L. E., Karatayev, A. Y., Marfurt, R. K., & Burks, R. L. (2006). Native and introduced Ampullariidae in North America: History, status, and ecology. Global advances in the ecology and management of golden apple snails, 73-112.

Kennedy, T. L. (2009). Current Population Trends of the Limpkin (Aramus guarauna) in Florida. Florida Scientist, 72(2), 134.

Howells, R. G., Burlakova, L. E., Karatayev, A. Y., Marfurt, R. K., & Burks, R. L. (2006). Native and introduced Ampullariidae in North America: History, status, and ecology. Global advances in the ecology and management of golden apple snails, 73-112.

Kennedy, T. L. (2009). Current Population Trends of the Limpkin (Aramus guarauna) in Florida. Florida Scientist, 72(2), 134.

Marzolf, N., Smith, C., & Golladay, S. (2019). Limpkin (Aramus guarauna) establishment following recent increase in nonnative prey availability in Lake Seminole, Georgia. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 131(1), 179-184.

Mills, E. L., & Laviolette, L. (2011). The Birds of Brier Island, Nova Scotia. Nova Scotian Institute of Science.

Mouritsen, H. (2001). Navigation in birds and other animals. Image and Vision Computing, 19(11), 713-731.

Posch, H., Garr, A. L., & Reynolds, E. (2013). The presence of an exotic snail, Pomacea maculata, inhibits growth of juvenile Florida apple snails, Pomacea paludosa. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 79(4), 383-385.

Rawlings, T. A., Hayes, K. A., Cowie, R. H., & Collins, T. M. (2007). The identity, distribution, and impacts of non-native apple snails in the continental United States. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 7(1), 97.

Ricciardi, A. (2015). Ecology of invasive alien invertebrates. In Thorp and Covich's Freshwater Invertebrates (pp. 83-91). Academic Press.

Smith, C., Golladay, S., Waters, M., & Clayton, B. OF LIMPKINS AND APPLE SNAILS: INVASIVE SPECIES, NOVEL ECOSYSTEMS, AND AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE.

Veit, R. R. (2000). Vagrants as the expanding fringe of a growing population. The Auk, 117(1), 242-246.

Wilcox, R. C., & Fletcher Jr, R. J. (2016). Experimental test of preferences for an invasive prey by an endangered predator: implications for conservation. PloS one, 11(11), e0165427.